Ron Swanson illustration by Sam Spratt. Parks and Rec fans come...

from Aziz is Bored

100+ people liked this

Ron Swanson illustration by Sam Spratt.

Parks and Rec fans come through again. Btw there’s a new episode tonight at 8:30/7:30c that was so fun to shoot. Adam Scott and I got to have a blast doing one of the best Ben/Tom stories yet. Watch it!

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

I think he nailed it

Add star

Oct 6, 2011 (2 days ago)

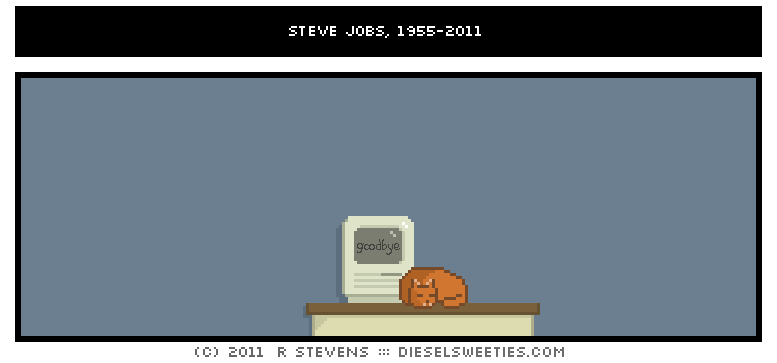

Steve Jobs, 1955-2011

from Diesel Sweeties webcomic by rstevens

100+ people liked this

My life would not exist in its current form had this guy not kicked the world's ass.

Add star

8:42 PM (4 hours ago)

Simple and elegant tribute to the late Steve...

Simple and elegant tribute to the late Steve Jobs by Jonathan Mak.

(Want more? See NOTCOT.org and NOTCOT.com)

Add star

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

Aaron Diaz Explains…

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

Storage on the Ceiling: Kiss Garage Clutter Goodbye The Family Handyman

Read Full Post

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

The Benjamin Franklin Effect

The Misconception: You do nice things for the people you like and bad things to the people you hate.

The Truth: You grow to like people for whom you do nice things and hate people you harm.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

Born in 1706 as the eighth of 17 children to a Massachusetts soap and candlestick maker, the chances Benjamin would go on to become a gentleman, scholar, scientist, statesman, musician, author, publisher and all-around general bad-ass were astronomically low, yet he did just that and more because he was a master of the game of personal politics.

Like many people full of drive and intelligence born into a low station, Franklin developed strong people skills and social powers. All else denied, the analytical mind will pick apart behavior, and Franklin became adroit at human relations. From an early age, he was a talker and a schemer – a man capable of guile, cunning and persuasive charm. He stockpiled a cache of cajolative secret weapons, one of which was the Benjamin Franklin Effect, a tool as useful today as it was in the 1730s and still just as counterintuitive. To understand it, let’s first rewind back to 1706.

Franklin’s prospects were dim. With 17 children, Josiah and Abiah Franklin could only afford two years of schooling for Benjamin. Instead, they made him work, and when he was 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James who was a printer in Boston. The printing business gave Benjamin the opportunity to read books and pamphlets. It was as if Ben Franklin was the one kid in the neighborhood who had access to the Internet. He read everything, and taught himself every skill and discipline one could absorb from text.

At 17, Franklin left Boston and started his own printing business In Philadelphia. At age 21, he formed a “club of mutual improvement” called the Junto. It was a grand scheme to gobble up knowledge. He invited working-class polymaths like himself who wanted to experiment in 1700s lifestyle design the chance to pool together their books and trade thoughts and knowledge of the world on a regular basis. They wrote and recited essays, held debates, and devised ways to acquire currency. Franklin used the Junto like a private consulting firm, a think tank, and he bounced ideas off of them so he could write and print better pamphlets. Franklin eventually founded the first subscription library in America and wrote it would make “the common tradesman and farmers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries,” not to mention, give him access to whatever books he wanted to buy. Genius.

By the 1730s Franklin was riding down an information superhighway of his own construction, and the constant stream of information made him a savvy politician in Philadelphia. A celebrity and an entrepreneur who printed both a newspaper and an almanac, Franklin had collected a few enemies by the time he ran for the position of clerk of the general assembly, but Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

As clerk, he could step into a waterfall of data coming out of the nascent government. He would record and print public records, bills, vote totals and other official documents. He would also make a fortune literally printing the state’s paper money. He won the race, but the next election wasn’t going to be as easy. Franklin’s autobiography never mentions this guy’s name, but according to the book when Franklin ran for his second term as clerk, one of his colleagues delivered a long speech to the legislature lambasting Franklin. Franklin still won his second term, but this guy truly pissed him off. In addition, this man was “a gentleman of fortune and education” who Franklin believed would one day become a person of great influence in the government. So, Franklin knew he had to be dealt with, and thus he launched his human behavior stealth bomber.

Franklin set out to turn his hater into a fan, but he wanted to do it without “paying any servile respect to him.” Franklin’s reputation as a book collector and library founder gave him a reputation as a man of discerning literary tastes, so Franklin sent a letter to the hater asking if he could borrow a selection from the his library, one which was a “very scarce and curious book.” The rival, flattered, sent it right away. Franklin sent it back a week later with a thank you note. Mission accomplished.

The next time the legislature met, the man approached Franklin and spoke to him in person for the first time. Franklin said the hater “ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.”

What exactly happened here? How can asking for a favor turn a hater into a fan? How can requesting kindness cause a person to change his or her opinion about you? The answer to what generates The Benjamin Franklin Effect is the answer to much more about why you do what you do.

Let’s start with your attitudes. Attitude is the psychological term for the the bundle of beliefs and feelings you experience toward a person, topic, idea, etc. without having to consciously think. Let’s try it out – Justin Beiber. Feel that? That’s your attitude toward him – a cascade of associations and feelings zipping along your neural net. Let’s try some more. Read this and then close your eyes – blueberry cheesecake. Nice, huh? One more – nuclear bomb. There you go again, a thunderhead of brain activity is telling you how you feel about that topic. Ask yourself this: how did you form that attitude?

For many things, your attitudes came from actions which led to observations which led to explanations which led to beliefs. It is well known in psychology the cart of behavior often gets before the horse of attitude. Your actions tend to chisel away at the raw marble of your persona, carving into being the self you experience day-to-day. It doesn’t feel that way though. To conscious experience, it feels like you are the one holding the chisel, motivated by existing thoughts and beliefs. It feels as though the person wearing your pants is performing actions consistent with your established character, yet there is plenty of research suggesting otherwise. The things you do often create the things you believe.The Truth: You grow to like people for whom you do nice things and hate people you harm.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

Benjamin Franklin knew how to deal with haters.Born in 1706 as the eighth of 17 children to a Massachusetts soap and candlestick maker, the chances Benjamin would go on to become a gentleman, scholar, scientist, statesman, musician, author, publisher and all-around general bad-ass were astronomically low, yet he did just that and more because he was a master of the game of personal politics.

Like many people full of drive and intelligence born into a low station, Franklin developed strong people skills and social powers. All else denied, the analytical mind will pick apart behavior, and Franklin became adroit at human relations. From an early age, he was a talker and a schemer – a man capable of guile, cunning and persuasive charm. He stockpiled a cache of cajolative secret weapons, one of which was the Benjamin Franklin Effect, a tool as useful today as it was in the 1730s and still just as counterintuitive. To understand it, let’s first rewind back to 1706.

Franklin’s prospects were dim. With 17 children, Josiah and Abiah Franklin could only afford two years of schooling for Benjamin. Instead, they made him work, and when he was 12 he became an apprentice to his brother James who was a printer in Boston. The printing business gave Benjamin the opportunity to read books and pamphlets. It was as if Ben Franklin was the one kid in the neighborhood who had access to the Internet. He read everything, and taught himself every skill and discipline one could absorb from text.

At 17, Franklin left Boston and started his own printing business In Philadelphia. At age 21, he formed a “club of mutual improvement” called the Junto. It was a grand scheme to gobble up knowledge. He invited working-class polymaths like himself who wanted to experiment in 1700s lifestyle design the chance to pool together their books and trade thoughts and knowledge of the world on a regular basis. They wrote and recited essays, held debates, and devised ways to acquire currency. Franklin used the Junto like a private consulting firm, a think tank, and he bounced ideas off of them so he could write and print better pamphlets. Franklin eventually founded the first subscription library in America and wrote it would make “the common tradesman and farmers as intelligent as most gentlemen from other countries,” not to mention, give him access to whatever books he wanted to buy. Genius.

By the 1730s Franklin was riding down an information superhighway of his own construction, and the constant stream of information made him a savvy politician in Philadelphia. A celebrity and an entrepreneur who printed both a newspaper and an almanac, Franklin had collected a few enemies by the time he ran for the position of clerk of the general assembly, but Franklin knew how to deal with haters.

As clerk, he could step into a waterfall of data coming out of the nascent government. He would record and print public records, bills, vote totals and other official documents. He would also make a fortune literally printing the state’s paper money. He won the race, but the next election wasn’t going to be as easy. Franklin’s autobiography never mentions this guy’s name, but according to the book when Franklin ran for his second term as clerk, one of his colleagues delivered a long speech to the legislature lambasting Franklin. Franklin still won his second term, but this guy truly pissed him off. In addition, this man was “a gentleman of fortune and education” who Franklin believed would one day become a person of great influence in the government. So, Franklin knew he had to be dealt with, and thus he launched his human behavior stealth bomber.

Franklin set out to turn his hater into a fan, but he wanted to do it without “paying any servile respect to him.” Franklin’s reputation as a book collector and library founder gave him a reputation as a man of discerning literary tastes, so Franklin sent a letter to the hater asking if he could borrow a selection from the his library, one which was a “very scarce and curious book.” The rival, flattered, sent it right away. Franklin sent it back a week later with a thank you note. Mission accomplished.

The next time the legislature met, the man approached Franklin and spoke to him in person for the first time. Franklin said the hater “ever after manifested a readiness to serve me on all occasions, so that we became great friends, and our friendship continued to his death.”

What exactly happened here? How can asking for a favor turn a hater into a fan? How can requesting kindness cause a person to change his or her opinion about you? The answer to what generates The Benjamin Franklin Effect is the answer to much more about why you do what you do.

Let’s start with your attitudes. Attitude is the psychological term for the the bundle of beliefs and feelings you experience toward a person, topic, idea, etc. without having to consciously think. Let’s try it out – Justin Beiber. Feel that? That’s your attitude toward him – a cascade of associations and feelings zipping along your neural net. Let’s try some more. Read this and then close your eyes – blueberry cheesecake. Nice, huh? One more – nuclear bomb. There you go again, a thunderhead of brain activity is telling you how you feel about that topic. Ask yourself this: how did you form that attitude?

At the lowest level, behavior-into-attitude conversion begins with impression management theory which says you present to your peers the person you wish to be. You engage in something economists call signaling by buying and displaying to your peers the sorts of things which give you social capital. If you live in the Deep South you might buy a high-rise pickup and a set of truck nuts. If you live in San Fransisco you might buy a Prius and a bike rack. Whatever are the easiest to obtain, loudest forms of the ideals you aspire to portray become the things you own, like bumper stickers signaling to the world you are in one group and not another. Those things then influence you to become the sort of person who owns them.

As a primate, you are keen to social cues which portend your possible ostracism from an in-group. In the wild, banishment equals death. So, it follows you work to feel included because the feeling of being left out, being the last to know, being the only one not invited to the party is a deep and severe slice into your emotional core. Anxiety over being ostracized, over being an outsider has driven the behavior of billions for millions of years. Impression management theory says you are always thinking about how you appear to others, even when there are no others around. In the absence of onlookers, deep in your mind, a mirror reflects back that which you have done, and when you see a person who has behaved in a way which could get you booted from your in-group, the anxiety drives you to seek a re-alignment. But, which came first? Your display or your belief? As a professional, do you feel compelled to wear a suit, or after donning a suit do you conduct yourself in a professional manner? Do you vote Democrat because you champion social programs, or do you champion social programs because you voted Democrat? The research says the latter in both cases. When you become a member of a group, or the fan of a genre, or the user of a product – those things have more influence on your attitudes than your attitudes have on them, but why?

“We are what we pretend to be, so we must be careful about what we pretend to be.” – Kurt VonnegutSelf perception theory says your attitudes are shaped by observing your own behavior, being unable to pinpoint the cause, and trying to make sense of it. You look back on a situation as if in an audience trying to understand your own motivations. You act as observer of your actions, a witness to your thoughts, and you form beliefs about your self based on those observations. Psychologists John Caciappo, Joseph R. Priester and Gary Bernston at the University of Chicago demonstrated this in 1993. They showed Chinese characters to people unfamiliar with Chinese ideographs and asked them to say whether they thought each character was positive or negative. Some people did this while lifting upward on the bottom of a table while others pushed downward against the surface.

On average, the characters rated highest across all subjects were the ones they saw while pulling upward, and the ones they rated as being most negative were the ones they saw while pushing down. Why? Because you unconsciously associate flexing with positive experiences and extension with negative. Pushing and pulling affects your perception because from the time you were an infant you have pulled toward you that which you desired and shoved into the distance that which repulsed you. The very word – repulsion – means to drive away. The neural connections are deep and dense. Self perception theory divides memories into declarative, or accessible to the conscious mind, and non-declarative, that which you store unconsciously. You intuitively understand how declarative memories shape, direct, and inform you. If you think about pumpkin spice muffins you feel warm and fuzzy. Self-perception theory posits non-declarative memories are just as powerful. You can’t access them, but they pulsate through your nervous system. Your posture, the temperature of the room, the way the muscles of your face are tensing – these things are informing your perception of who you are and what you think. Drawing near is positive. Pushing away is negative. Self perception theory shows you unconsciously observe your own actions and then explain them in a pleasing way without ever realizing it. Benjamin Franklin’s enemy observed himself performing a generous and positive act by offering the treasured tome to his rival, and then he unconsciously explained his own behavior to himself. He must not have hated Franklin after all, he thought; why else would he do something like that?

On average, the characters rated highest across all subjects were the ones they saw while pulling upward, and the ones they rated as being most negative were the ones they saw while pushing down. Why? Because you unconsciously associate flexing with positive experiences and extension with negative. Pushing and pulling affects your perception because from the time you were an infant you have pulled toward you that which you desired and shoved into the distance that which repulsed you. The very word – repulsion – means to drive away. The neural connections are deep and dense. Self perception theory divides memories into declarative, or accessible to the conscious mind, and non-declarative, that which you store unconsciously. You intuitively understand how declarative memories shape, direct, and inform you. If you think about pumpkin spice muffins you feel warm and fuzzy. Self-perception theory posits non-declarative memories are just as powerful. You can’t access them, but they pulsate through your nervous system. Your posture, the temperature of the room, the way the muscles of your face are tensing – these things are informing your perception of who you are and what you think. Drawing near is positive. Pushing away is negative. Self perception theory shows you unconsciously observe your own actions and then explain them in a pleasing way without ever realizing it. Benjamin Franklin’s enemy observed himself performing a generous and positive act by offering the treasured tome to his rival, and then he unconsciously explained his own behavior to himself. He must not have hated Franklin after all, he thought; why else would he do something like that?“A world that can be explained even with bad reasons is a familiar world. But, on the other hand, in a universe suddenly divested of illusions and lights, man feels an alien, a stranger. His exile is without remedy since he is deprived of the memory of a lost home or the hope of a promised land. This divorce between man and his life, the actor and his setting, is properly the feeling of absurdity.” – Albert CamusMany psychologists would explain the Benjamin Franklin effect through the lens of cognitive dissonance, a giant theory made up of thousands of studies which have pinpointed a menagerie of mental stumbling blocks includingconfirmation bias, hindsight bias, the backfire effect, the sunk cost fallacy, and many more, but as a general theory it describes something you experience every day.

Sometimes you can’t find a logical, moral or socially acceptable explanation for your actions. Sometimes your behavior runs counter to the expectations of your culture, your social group, your family or even the person you believe yourself to be. In those moments you ask, “Why did I do that?” and if the answer damages your self-esteem, a justification is required. You feel like a bag of sand has ruptured in your head, and you want relief. You can see the proof in an MRI scan of someone presented with political opinions which conflict with their own. The brain scans of a person shown statements which oppose their political stance show the highest areas of the cortex, the portions responsible for providing rational thought, get less blood until another statement is presented which confirms their beliefs. Your brain literally begins to shut down when you feel your ideology is threatened. Try it yourself. Watch a pundit you hate for 15 minutes. Resist the urge to change the channel. Don’t complain to the person next to you. Don’t get online and rant. Try and let it go. You will find this is excruciatingly difficult.

In 1957, psychologist Leon Festinger infiltrated a doomsday cult led by Dorothy Martin who called herself Sister Thedra. She convinced her followers in Chicago an alien spacecraft would suck them up and fly away right as a massive flood ended the human race on December 21, 1954. Many of her followers gave away everything they owned, including their homes, as the day approached. Festinger wanted to see what would happen when the spaceship and the flood failed to appear. Festinger hypothesized the cult members faced the choice of either seeing themselves as foolish rubes or assuming their faith had spared them. Would the cult members keep their weird beliefs beyond the date the world was supposed to end and become even more passionate as had so many groups before them under similar circumstances? Of course they did. Once enough time had passed they could be pretty sure no spaceships were coming, they began to contact the media with the good news: their positive energy had convinced God to spare the Earth. They had freaked out and then found a way to calm down. Festinger saw their heightened state of arousal as a special form of anxiety – cognitive dissonance. When you experience this arousal it is as if two competing beliefs are struggling in a mental bar fight, knocking over chairs and smashing bottles over each other’s heads. It feels awful, and the feeling persists until one belief knocks the other out cold.

Festinger went on to study cognitive dissonance in a controlled environment. He and his colleague Judson Mills set up an experiment at Stanford in which they invited students to join an exclusive club studying the psychology of sex. They told students to get in the group they would have to pass an initiation. They secretly divided the applicants into two groups, one read sexual terms from a dictionary out loud to a scientist, and the other read aloud entire passages from the most famous romance novel of all time, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Remember, this was 1950s America, so either task was massively embarrassing, but reading aloud sex scenes filled with F and C-bombs evoked a megadose of awkwardness. After the initiation, both groups listened to an audio recording of the sort of group discussion they had just earned the ability to join. The scientists made sure the discussion they heard was as dry and boring and un-sexy as they could make it, going so far as to focus the sex talk on the mating habits of birds. They then had the students rate the talk. The people who read from the dictionary told Festinger the sex group was a drag and probably not something they’d like to continue attending. The romance novel group said the group was exciting and interesting and something they could not wait to begin. Same tape, two realities.

“These findings do not mean that people enjoy painful experiences, such as filling out their income-tax forms, or that people enjoy things because they are associated with pain. What they do show is that if a person voluntarily goes through a difficult or a painful experience in order to attain some goal or object, that goal or object becomes more attractive.” – Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson from their book Mistakes Were Made (But Not by Me)Festinger and another colleague, J. Merrill Carlsmith, pushed ahead with this research in 1959 in what is now considered the landmark study which launched the next 40 years of investigation into the phenomenon, an investigation which continues right up until today.

Students at Stanford University signed up for a two-hour experiment called “Measures of Performance” as a requirement to pass a class. Researchers divided them into two groups. One was told they would receive $1, or about $8 in today’s money. The other group was told they would receive $20, or about $150 in today’s money. The scientists then explained the students would be helping improve the research department by evaluating a new experiment. They were then led into a room where they had to use one hand to place wooden spools into a tray and remove them over and over again. A half-hour later, the task changed to turning square pegs clockwise on a flat board one-quarter spin at a time for half an hour. All the while, an experimenter watched and scribbled. It was one hour of torturous tedium with a guy watching and taking notes. After the hour was up, the researcher asked the student if he could do the school a favor on their way out by telling the next student scheduled to perform the tasks who was waiting outside that the experiment was fun and interesting. Finally, after lying, people in both groups – one with $1 in their pocket and one with $20 – filled out a survey in which they were asked their true feelings about the study. What do you think they said? Here’s a hint – one group not only lied to the person waiting outside but went on to report they loved repeatedly turning little wooden knobs. Which one do you think internalized the lie? On average, the people paid $1 reported the study was stimulating. The people paid $20 reported what they just went thorough was some astoundly boring-ass shit. Why the difference?

According to Festinger, both groups lied about the hour, but only one felt cognitive dissonance. It was as if the group paid $20 thought, “Well, that was awful, and I just lied about it, but they paid me a lot of money, so…no worries.” Their mental discomfort was quickly and easily dealt with by a nice external justification. The group paid $1 had no outside justification, so they turned inward. They altered their beliefs to salve their cerebral sunburn. This is why volunteering feels good and unpaid interns work so hard. Without an obvious outside reward you create an internal one.

That’s the cycle of cognitive dissonance, a painful confusion about who you are gets resolved by seeing the world in a more satisfying way. As Festinger said, you make “your view of the world fit with how you feel or what you’ve done.” When you feel anxiety over your actions, you will seek to lower the anxiety by creating a fantasy world in which your anxiety can’t exist, and then you come to believe the fantasy is reality just as Benjamin Franklin’s rival did. He couldn’t possibly have lent a rare book to a guy he didn’t like, so he must actually like him. Problem solved.

So, has the Benjamin Franklin Effect itself ever been tested? Yes. Jim Jecker and David Landy, building on the work of Festinger, conducted an experiment in 1969 which had actors pretend to be a scientist and a research secretary conducting a study. Subjects came into the lab believing they were going to perform psychological tests in which they could win money. The actor pretending to be the scientist attempted to make the subjects hate him by being rude and demanding as he administered a rigged series of tests. Each subject succeeded 12 times no matter what, but one group won 60 cents in total and the other won $3, which would be about $5 and $20 adjusted for inflation. After the experiment, the actor told the subjects to walk up the stairs and fill out a questionnaire. At this point, the actor stopped one third of all the subjects right as they were leaving and asked for the money back. He told them he was paying for the experiment out of his own pocket and could really use the favor because the study was in danger of running out of funds. Everyone agreed. Another third left the room and filled out the questionnaire in front of an actor pretending to be a secretary. As they were about to answer the questions, the secretary asked if they would please donate their winnings back into the research department fund as they were strapped for cash. Again, everyone agreed. The final third got to leave with their winnings without any hassle.

The real study was to see what the subjects thought of the asshole researcher after doing him a favor. The questionnaire asked how much they liked him on a scale from 1 to 12. The people who won 60 cents ($5) were barely affected, but the people who won $3 ($20) saw things differently. On average, those who got to leave with their money rated him as a 5.8. The ones who did the secretary a favor gave him a 4.4. The ones who did the researcher a favor gave him a 7.2, suggesting the Benjamin Franklin Effect made them like him far more than the other two groups. The people who lost the most money and then did the stranger a favor suffered the most dissonance, according to researchers, and thus adjusted their beliefs the most.

Benjamin Franklin’s hater came to like Franklin after doing him a favor, but what if he had done him harm instead? In 1971, at the University of North Carolina, psychologists John Schopler and John Compere asked students to help with an experiment. They had their subjects administer learning tests to accomplices pretending to be other students. The subjects were told the learners would watch as the teachers used sticks to tap out long patters on a series of wooden cubes. The learners would then be asked to repeat the patterns. Each teacher was to try out two different methods on two different people, one at a time. In one run, the teachers would offer encouragement when the learner got the patterns correct. In the other run of the experiment, the teacher would insult and criticize the learner when they messed up. Afterward, the teachers filled out a debriefing questionnaire which included questions about how attractive (as a human being, not romantically) and likable the learners were. Across the board, the subjects who received the insults were rated as less attractive than the ones who got encouragement. The teachers’ behavior created their perception. You tend to like the people to whom you are kind and dislike the people to whom you are rude. From the Stanford Prison Experiment to Abu Ghraib, to concentration camps and the attitudes of soldiers spilling blood, mountains of evidence suggest behaviors create attitudes when harming just as they do when helping. Jailers come to look down on inmates; camp guards come to dehumanize their captives; soldiers create derogatory terms for their enemies. It’s difficult to hurt someone you admire. It’s even more difficult to kill a fellow human being. Seeing the casualties you create as something less than you, something deserving of damage, makes it possible to continue seeing yourself as a good and honest person, to continue being sane.

The Benjamin Franklin Effect is the result of your concept of self coming under attack. Every person develops a persona, and that persona persists because inconsistencies in your personal narrative get rewritten, redacted and misinterpreted. If you are like most people, you have high self-esteem and tend to believe you are above average in just about every way. It keeps you going, keeps your head above water, so when the source of your own behavior is mysterious you will confabulate a story which paints you in a positive light. If you are on the other end of the self-esteem spectrum and tend to see yourself as undeserving and unworthy, you will rewrite nebulous behavior as the result of attitudes consistent with the persona of an incompetent person, deviant, or whatever flavor of loser you believe yourself to be. Successes will make you uncomfortable so you will dismiss them as flukes. If people are nice to you, you will assume they have ulterior motives or are mistaken. Whether you love or hate your persona, you protect the self with which you’ve become comfortable. When you observe your own behavior, or feel the gaze of an outsider, you manipulate the facts so they match your expectations.

Most animals just do what they do. Sea cucumbers and aardvarks don’t think about their actions, don’t feel shame, pride or regret. You do, even when there is no reason to. If you look back on a behavior, thought or emotion and feel befuddled, you feel an intense desire to explain it, and that explanation can affect your future behavior, your future thoughts, your future feelings.

Pay attention to when the cart is getting before the horse. Notice when a painful initiation leads to irrational devotion, or when unsatisfying jobs start to seem worthwhile. Remind yourself pledges and promises have power, as do uniforms and parades. Remember in the absence of extrinsic rewards you will seek out or create intrinsic ones. Take into account the higher the price you pay for your decisions the more you value them. See that ambivalence becomes certainty with time. Realize lukewarm feelings become stronger once you commit to a group, club or product. Be wary of the roles you play and the acts you put on, because you tend to fulfill the labels you accept. Above all, remember the more harm you cause, the more hate you feel, and the more kindness you deal into the world the more you come to love the people you help.

“This is another instance of the truth of an old maxim I had learned, which says, ‘He that has once done you a kindness will be more ready to do you another, than he whom you yourself have obliged.’ And it shows how much more profitable it is prudently to remove, than to resent, return, and continue inimical proceedings.” - Benjamin Franklin

You Are Not So Smart – The Book

You Are Not So Smart – The Book If you buy one book this year…well, I suppose you should get something you’ve had your eye on for a while. But, if you buy two or more books this year, might I recommend one of them be a celebration of self delusion? Give the gift of humility (to yourself or someone else you love). Watch the trailer.

Preorder now: Amazon - Barnes and Noble – iTunes - Book A Million

Links:

Franklin’s Autobiography

The Wicker Metastudy

The Push Pull Study

The Boring Knobs Study

The Franklin Effect Study

Moral Hypocrisy Study

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

Oral sex might cause more throat cancer than smoking [Holy Crap Wtf]

A study published in yesterday's Journal of Clinical Oncology reveals that as many as 72 percent of throat tumors in men may be linked to the human papillomavirus, commonly known as HPV. The researchers hypothesize that the virus spreads predominately via oral sex, and that it may already account for more cases of throat cancer than smoking. More »

Add star

Oct 7, 2011 (23 hours ago)

Steve Jobs and the Reserved Seat

That picture pretty much says it all. During the “Let’s Talk iPhone” event on Tuesday, I kept noticing that seat. “Reserved.” It was weird that the camera kept panning to that shot of the front row in Town Hall.

The room was packed tight with journalists, but there was that one seat left empty in the front row next to all of the other Apple executives. Steve’s seat.

I don’t know for sure if that seat was left empty for Steve or not, but I can only imagine that it had to have been. In a way, that reserved seat summarizes the core of who Apple is as a company and group of people.

Apple’s tribute page to Steve Jobs says that, “his spirit will forever be the foundation of Apple.” During Tuesday’s keynote, I kept wondering why the team of presenters seemed so subdued — especially Tim Cook and Phil Schiller.

I couldn’t put my finger on it then, but looking back, it’s obvious that Cook and the rest of the executive team knew that their dear friend and leader was on the verge of death. But there were still products to be announced, and as they say, “the show must go on.”

So, Cook, Forstall, Cue, and Schiller all gave us an Apple event filled with news on the state of Apple, iCloud, iOS 5, the iPod, and the iPhone 4S. Whether you like the 4S or not, you can’t deny that Apple delivered on Tuesday. Apple delivered without Steve.

But that reserved seat still says something. It says that there will always be a place for Steve at Apple. It says that, although Steve may be gone for good now, his impact and influence will always be appreciated and cherished by the company he invested relentlessly in for so many years. His spirit lives on through his products and the people he raised up to lead Apple into the future.

There will always be a seat reserved for you, Steve.

Similar Posts:

- Watch Apple’s “Let’s Talk iPhone” Event Online

- How Did Tim Cook Do Today? [Opinion]

- Steve Jobs Slowly Beginning to Let Go of the Reins at Apple

- Scott Forstall Talks iOS Numbers: Quarter Billion Devices Sold and iPad is Number One [Let's Talk iPhone]

- Munster: Jobs’ Absence Makes Macworld A Snore

Add star

Oct 5, 2011 (3 days ago)

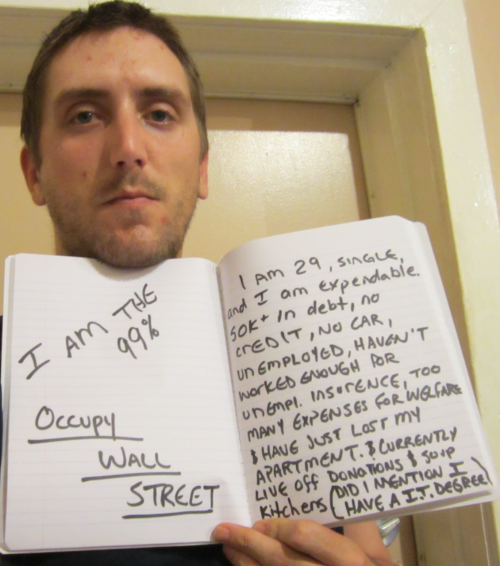

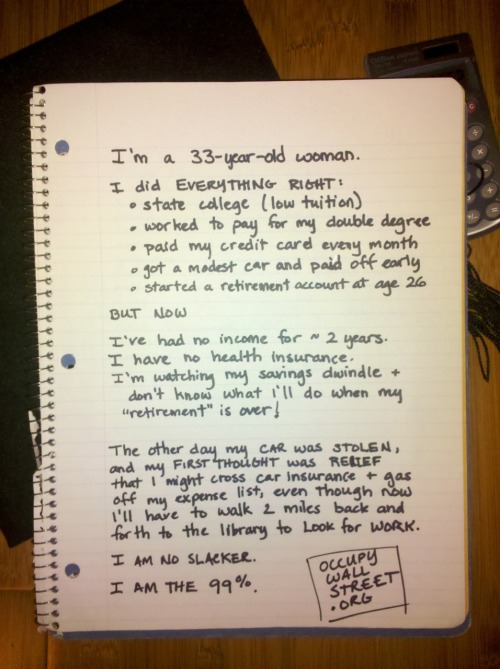

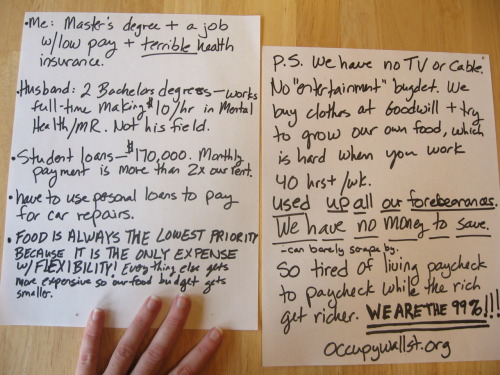

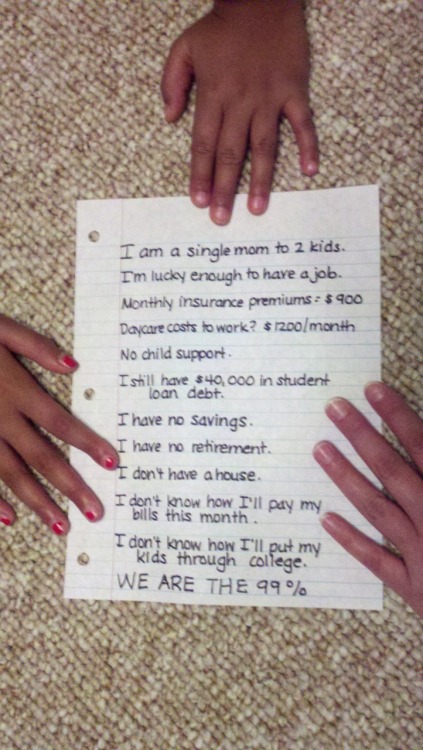

Let’s make New Zealand the 1 percent

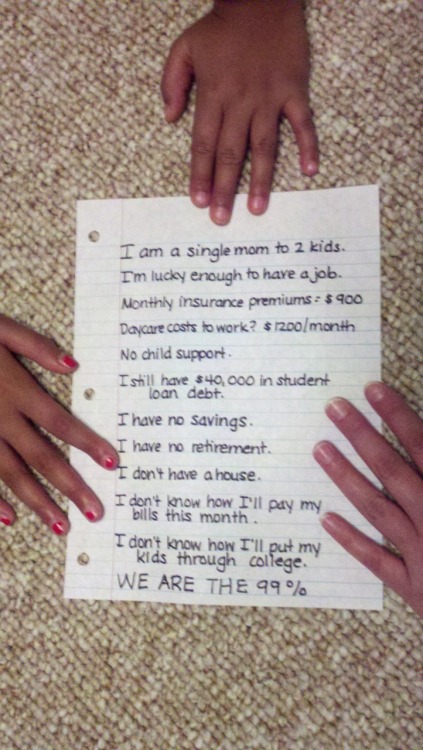

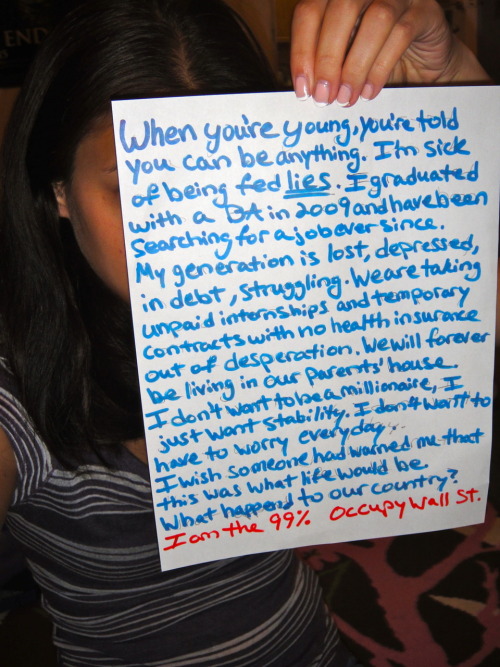

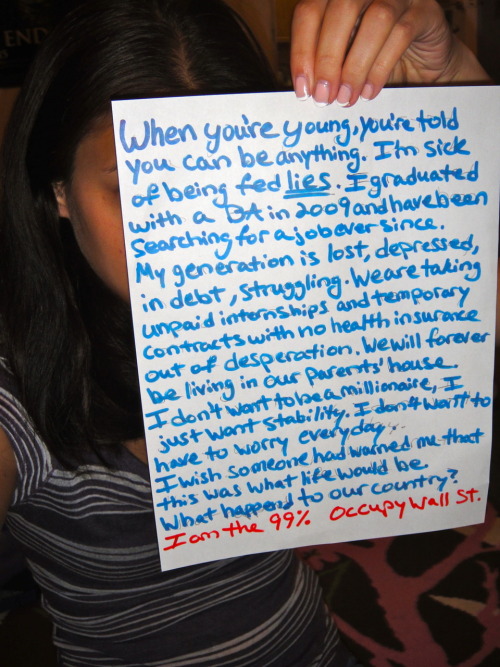

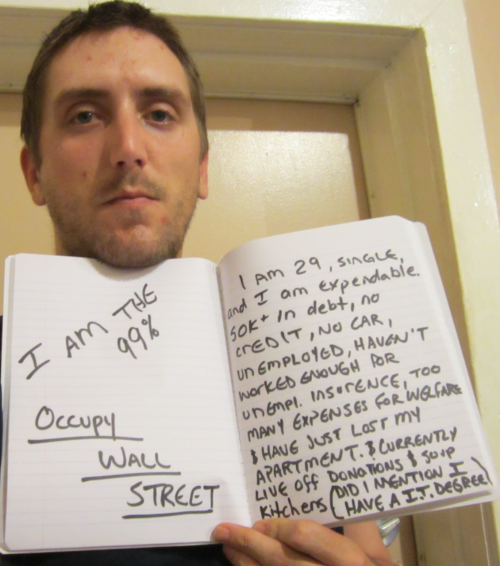

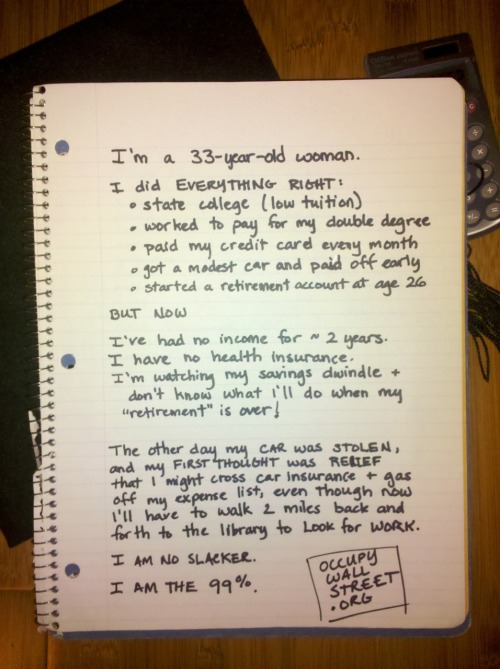

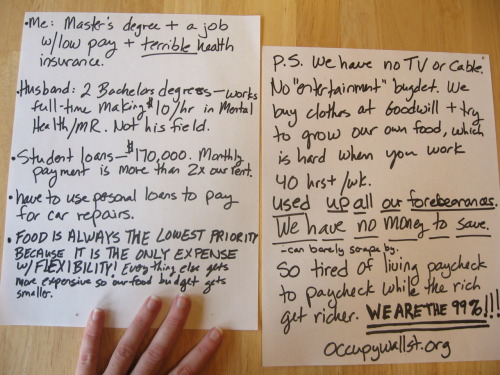

The posts at WeAreThe99Percent are sobering, shocking.

They are some of people caught in the downward spiral of the US economy, but in reality it’s been happening for years as the split between the wealthy and the ‘middle class’ gets increasingly large.

The stories are of cripplingly high health care costs that destroy families, of foreclosures on mortgages and of the obvious result of years of banks pushing debt to customers.

There are also strong themes of ever-increasingly expensive education that is of diminishing value in the job market, and people are loaded up with tens of thousands in debt and low paid or no jobs.

These are signs of a society that is failing its people, and a strong articulation of exactly what the Occupy Wall Street movement is all about.

Is this the real Tea Party?

David Koch, second richest man in New York is apparently a cornerstone funder of the Tea Party, and he and his brother hold strong Libertarian views. Some of those views I regard as part of a fair society (legalisation of prostitution and drugs, gay marriage, removal of farm subsidies) but some are downright dangerous (removal ofSocial Security, the Federal Reserve Board and welfare).

The Tea Party movement was arguably taken over and certainly accelerated by Fox News into what seems to be a nutty right wing group, but the mass membership are driven by much of the same concerns as Occupy Wall St.

We are faced with interesting times over the next weeks – will the Tea Party followers increasingly realise that they have been duped?

This newer Occupy Wall Street movement appears to be a genuine one, rising from a sea of frustration from people who are under-served and with little prospect. It started from a suggestion in a email from Adbusters to their readers, and seems to have no leaders.

Many of the participants made mistakes, perhaps taking on too much debt or studying the wrong degrees. But many more of them have done what society demanded of them, attending university, paying insurance, buying a car – and then got clobbered. The safety net in the USA has many holes, and doesn’t last for long.

The problems are not so simple

A lot of what the financial industry (Wall Street) does is good, even the slicing and dicing of mortgages up into CDOs was a good idea. What was not good was the pricing of those CDOs, the way they were sold and the way that mortgages were granted to people who realistically had no hope of ever paying them off. What is worse is the propensity to clip the ticket for increasing amounts. The short term dealmaking, get the money now nature of the street has its place as lubricant for helping businesses make tough decisions, but it encourages unacceptable banking practices in the long run. The US really does need to reinstitute the separation of retail banks and investment/trading banks, and bring in adult supervision.

The financial institutions do not stand alone in being recipients of fury. US corporations there are paying an increasingly small share of the overall tax burden, with some such as GE earning billions and paying little or no tax, or even receiving rebates. This is the result from years of corporate lobbying for tweaks in tax law, and the results are repugnant. The USA could learn from New Zealand should dramatically simplify their tax code, much like Roger Douglas did in 1984, and introduce a GST.

That’s not to say that that everyone on Wall Street is repugnant, or that even they see themselves doing wrong – far from it. It’s a game where the choices are laid out in front of you, and if you excel then the money will come. It’s a game where the amount of money flying around is so high that it’s relatively easy to ensure that a little sticks to those making the transaction.

Financiers however play within rules set for them by legislators in Washington DC. Those legislators are there thanks to a host of donations from thousands of people, but some of the larger amounts come from companies and individuals on Wall Street. That mixture of politics and money has lifted the concerns of corporations and diminished the relative concerns of individuals. It’s got to stop, but a recent Supreme Court decision actually went the other way – defending the right of corporations to get involved in elections.

A decent society is decent to everyone, regardless of whether they are old, young, sick, or healthy, or even whether they chose at times not to abide by our rules. I reject completely the idea of living in a society that accepts homelessness, that does not care for mentally and that locks up people for offenses that are relatively harmless. We humans are better than that.

Being part of the 1 percent

I was lucky enough to study and work at two elite USA institutions – Yale University and McKinsey & Co. The experiences at those two places were outstanding – the level of education at top schools and the scale of the work available in the USA at the top end far exceeds anything here. I helped, for example, 2 organisations with over $500 billion in assets at the highest level. I was taught by people that wrote the books we study from and met a group of ultra smart, globally savvy, fun and driven people. In short I was becoming part of the 1 percent, even though for four of my five years in the USA I was in debt, and even though my income paled in comparison with those on Wall street.

I deliberately chose not to apply for Wall Street jobs during my MBA, as despite the fun of playing with large sums of money there seemed to be little reward beyond chasing the money god. I was lucky (or unlucky) enough to temp for a few months in a bank that sold structured financial products in London, counting the amount of money that the bankers had made over and above the internally calculated value of those products. It was a calculation of a knowledge advantage, and the units were millions of dollar per day. Those bankers or traders were seen as the elite within the bank people, but in reality they were arseholes, and like everyone else there, including me, they were dedicated to making money and to little else. I was lucky because I managed to get kicked out relatively quickly.

Being part of the 1 percent as a professional isn’t easy either. You are expected to work incredibly hard, maintain a certain sense of decorum and not rock the boat. It helps to have gone to the right school, for undergraduate and graduate studies, if not before. You don’t get much in the way of holidays, and are expected to be on call at all times.

I managed, courtesy of the last recession, to again break away from the USA corporate scene.

New Zealand

Meanwhile in New Zealand many are experiencing at some of the negative impact of the GFC, though I am unsure as to how bad it really is. Compound that with the hammering that Christchurch took, and while we are just getting on with it, we potentially have some real problems.

However we are blessed with a society and politics that, ACT party notwithstanding, generally and genuinely finds it unacceptable to treat people so harshly.

We are seeing increasing disparity between the wealthy and the rest in NZ, and we therefore need to doubly continue to ensure that the social welfare safety net is working. That means free or cheap education and health, as fundamental rights, it means a living income for everyone regardless of their circumstance and it means making sure we don’t have a situation where housing is unaffordable and can create catastrophic losses for families.

At the same time we need a society and economy where businesses can start, nurture, grow and prosper. We already have some good elements in our tax system, but there is a way to go before we get a fair tax system that rewards entrepreneurialism and has minimal loopholes. We don’t, for example, tax capital gains at all here. A simple across the board 20% tax on capital gains worked well in the USA for many years, and a tax I would welcome here, excluding only primary residences.

While there are problems, we have a good society here, and many live the life that many of the 1 percenters do not manage to live in the USA. We have the lifestyle many in the world dream of, while we have the ideal economy to start and grow businesses.

So what can we do about it here in NZ?

There is not a lot we can do about US policy, and it is senseless to get buried in US politics as it is something which we can and should not try to influence. Also it is, as far as I know, illegal for non-citizens to donate to campaigns.

But we can make sure that we don’t follow in the footsteps of the US by making sure we stay vigilant on the things that make our society great. We missed for example, decent regulation of finance companies, resulting in the loss of billions. We succeeded though in standing up to banks, and their current strength is partially a function of that.

Why can’t we make our 1% into 100%? Why not aim to make New Zealanders the envy of the world, combining a (minimum) decent living with a vibrant economy and the world’s best lifestyle.

It’s something worth pushing for, and here are some of the basic elements I believe we need to (continue to) push for*:

*Note that I don’t believe, for now anyway, in a financial transaction tax as has been mooted by some. The call is for a, say, 50 cent tax on each financial transaction. The difficulty is in understanding exactly what a transaction is. Traders could simply gather up all trades for a day between themselves and other institutions and call them one transaction. Alternatively if the tax was based on the number of securities exchanging hands, then bankers would simply construct products with higher face value and lower numbers of securities. And so on. For every tax a financial product can be created off-market that avoids the tax, but only the largest banks will be able to do this. The smaller investors would pay the tax regardless.

Filed under: NZ Business

They are some of people caught in the downward spiral of the US economy, but in reality it’s been happening for years as the split between the wealthy and the ‘middle class’ gets increasingly large.

The stories are of cripplingly high health care costs that destroy families, of foreclosures on mortgages and of the obvious result of years of banks pushing debt to customers.

There are also strong themes of ever-increasingly expensive education that is of diminishing value in the job market, and people are loaded up with tens of thousands in debt and low paid or no jobs.

These are signs of a society that is failing its people, and a strong articulation of exactly what the Occupy Wall Street movement is all about.

Is this the real Tea Party?

David Koch, second richest man in New York is apparently a cornerstone funder of the Tea Party, and he and his brother hold strong Libertarian views. Some of those views I regard as part of a fair society (legalisation of prostitution and drugs, gay marriage, removal of farm subsidies) but some are downright dangerous (removal ofSocial Security, the Federal Reserve Board and welfare).

The Tea Party movement was arguably taken over and certainly accelerated by Fox News into what seems to be a nutty right wing group, but the mass membership are driven by much of the same concerns as Occupy Wall St.

We are faced with interesting times over the next weeks – will the Tea Party followers increasingly realise that they have been duped?

This newer Occupy Wall Street movement appears to be a genuine one, rising from a sea of frustration from people who are under-served and with little prospect. It started from a suggestion in a email from Adbusters to their readers, and seems to have no leaders.

Many of the participants made mistakes, perhaps taking on too much debt or studying the wrong degrees. But many more of them have done what society demanded of them, attending university, paying insurance, buying a car – and then got clobbered. The safety net in the USA has many holes, and doesn’t last for long.

The problems are not so simple

A lot of what the financial industry (Wall Street) does is good, even the slicing and dicing of mortgages up into CDOs was a good idea. What was not good was the pricing of those CDOs, the way they were sold and the way that mortgages were granted to people who realistically had no hope of ever paying them off. What is worse is the propensity to clip the ticket for increasing amounts. The short term dealmaking, get the money now nature of the street has its place as lubricant for helping businesses make tough decisions, but it encourages unacceptable banking practices in the long run. The US really does need to reinstitute the separation of retail banks and investment/trading banks, and bring in adult supervision.

The financial institutions do not stand alone in being recipients of fury. US corporations there are paying an increasingly small share of the overall tax burden, with some such as GE earning billions and paying little or no tax, or even receiving rebates. This is the result from years of corporate lobbying for tweaks in tax law, and the results are repugnant. The USA could learn from New Zealand should dramatically simplify their tax code, much like Roger Douglas did in 1984, and introduce a GST.

That’s not to say that that everyone on Wall Street is repugnant, or that even they see themselves doing wrong – far from it. It’s a game where the choices are laid out in front of you, and if you excel then the money will come. It’s a game where the amount of money flying around is so high that it’s relatively easy to ensure that a little sticks to those making the transaction.

Financiers however play within rules set for them by legislators in Washington DC. Those legislators are there thanks to a host of donations from thousands of people, but some of the larger amounts come from companies and individuals on Wall Street. That mixture of politics and money has lifted the concerns of corporations and diminished the relative concerns of individuals. It’s got to stop, but a recent Supreme Court decision actually went the other way – defending the right of corporations to get involved in elections.

A decent society is decent to everyone, regardless of whether they are old, young, sick, or healthy, or even whether they chose at times not to abide by our rules. I reject completely the idea of living in a society that accepts homelessness, that does not care for mentally and that locks up people for offenses that are relatively harmless. We humans are better than that.

Being part of the 1 percent

I was lucky enough to study and work at two elite USA institutions – Yale University and McKinsey & Co. The experiences at those two places were outstanding – the level of education at top schools and the scale of the work available in the USA at the top end far exceeds anything here. I helped, for example, 2 organisations with over $500 billion in assets at the highest level. I was taught by people that wrote the books we study from and met a group of ultra smart, globally savvy, fun and driven people. In short I was becoming part of the 1 percent, even though for four of my five years in the USA I was in debt, and even though my income paled in comparison with those on Wall street.

I deliberately chose not to apply for Wall Street jobs during my MBA, as despite the fun of playing with large sums of money there seemed to be little reward beyond chasing the money god. I was lucky (or unlucky) enough to temp for a few months in a bank that sold structured financial products in London, counting the amount of money that the bankers had made over and above the internally calculated value of those products. It was a calculation of a knowledge advantage, and the units were millions of dollar per day. Those bankers or traders were seen as the elite within the bank people, but in reality they were arseholes, and like everyone else there, including me, they were dedicated to making money and to little else. I was lucky because I managed to get kicked out relatively quickly.

Being part of the 1 percent as a professional isn’t easy either. You are expected to work incredibly hard, maintain a certain sense of decorum and not rock the boat. It helps to have gone to the right school, for undergraduate and graduate studies, if not before. You don’t get much in the way of holidays, and are expected to be on call at all times.

I managed, courtesy of the last recession, to again break away from the USA corporate scene.

New Zealand

Meanwhile in New Zealand many are experiencing at some of the negative impact of the GFC, though I am unsure as to how bad it really is. Compound that with the hammering that Christchurch took, and while we are just getting on with it, we potentially have some real problems.

However we are blessed with a society and politics that, ACT party notwithstanding, generally and genuinely finds it unacceptable to treat people so harshly.

We are seeing increasing disparity between the wealthy and the rest in NZ, and we therefore need to doubly continue to ensure that the social welfare safety net is working. That means free or cheap education and health, as fundamental rights, it means a living income for everyone regardless of their circumstance and it means making sure we don’t have a situation where housing is unaffordable and can create catastrophic losses for families.

At the same time we need a society and economy where businesses can start, nurture, grow and prosper. We already have some good elements in our tax system, but there is a way to go before we get a fair tax system that rewards entrepreneurialism and has minimal loopholes. We don’t, for example, tax capital gains at all here. A simple across the board 20% tax on capital gains worked well in the USA for many years, and a tax I would welcome here, excluding only primary residences.

While there are problems, we have a good society here, and many live the life that many of the 1 percenters do not manage to live in the USA. We have the lifestyle many in the world dream of, while we have the ideal economy to start and grow businesses.

So what can we do about it here in NZ?

There is not a lot we can do about US policy, and it is senseless to get buried in US politics as it is something which we can and should not try to influence. Also it is, as far as I know, illegal for non-citizens to donate to campaigns.

But we can make sure that we don’t follow in the footsteps of the US by making sure we stay vigilant on the things that make our society great. We missed for example, decent regulation of finance companies, resulting in the loss of billions. We succeeded though in standing up to banks, and their current strength is partially a function of that.

Why can’t we make our 1% into 100%? Why not aim to make New Zealanders the envy of the world, combining a (minimum) decent living with a vibrant economy and the world’s best lifestyle.

It’s something worth pushing for, and here are some of the basic elements I believe we need to (continue to) push for*:

- A simple social welfare system that ensures everyone gets a living wage, regardless of the reason they need help

- Low or no income taxes for those earning under a minimum amount

- Free or near free high and consistent quality education for those who cannot afford otherwise

- Free or near free health care for those who cannot afford otherwise

- A flat capital gains tax (say 20%) on all capital gains except for sale of the primary residence

- Decriminalization of all and legalization of certain drugs, to drive safer drug taking though better messaging, less drug taking (Portugal example), higher income from tax on drug sales and removal of the largest cause of crime from the mandate of police.

- Constant effort to maintain our short election campaigns and campaign financing that cannot be influenced by wealth of individuals or corporations.

- Constant effort to increasingly simplify tax law, making it as easy for corporates to understand their income liability as it it is with GST.

- Firm and fair regulation from well educated and informed regulators of companies that take money from investors.

- Continued celebration of individuals who make it big by building great companies with strong values, and condemnation of those who create wealth through financial trickery and do not give back.

*Note that I don’t believe, for now anyway, in a financial transaction tax as has been mooted by some. The call is for a, say, 50 cent tax on each financial transaction. The difficulty is in understanding exactly what a transaction is. Traders could simply gather up all trades for a day between themselves and other institutions and call them one transaction. Alternatively if the tax was based on the number of securities exchanging hands, then bankers would simply construct products with higher face value and lower numbers of securities. And so on. For every tax a financial product can be created off-market that avoids the tax, but only the largest banks will be able to do this. The smaller investors would pay the tax regardless.

Filed under: NZ Business

Add star

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar